As wildfire risk grows, will planting trees work to offset carbon emissions?

In general, younger trees are more susceptible to fires, which is bad news for Canada’s efforts to plant them as a way to meet its climate goals, like in the 2 Billion Tree project. But both fires and forests are complex.

In early June, a wildfire took a small, 100-hectare bite out of the BigCoast Forest Climate Initiative project, located in British Columbia, Bloomberg reported. Run by Mosaic Forest Management Corporation, the 40,000-hectare project involves planting trees to soak up and store carbon from the atmosphere.

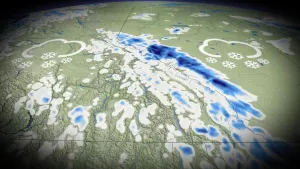

These numbers are just a small part of the wildfires that Canada has seen this year, which covered more than 12 million hectares of land in Canada this year, and released more than 249 million tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere, as of mid-July.

Across Canada, there are many similar efforts to plant new trees and new forested areas as carbon sinks to help the country reach its climate goals. These include the federal government’s 2 Billion Trees program (2BT) — which partners with and provides funding to interested public and private groups — Ontario’s 50 Million Tree Program and various companies that plant trees to offset their emissions.

However, if Canada’s future holds yet more severe wildfire years, the carbon sequestration benefits of these young trees and forested areas is in question. In some cases, young trees may be more susceptible to death by fires, and can end up releasing what carbon they stored back into the air.

Some experts told The Weather Network that a plot of forested, or reforested, land’s wildfire risk varies depending on tree age, tree type, climate, and a host of other factors. Others experts were perhaps more critical.

“It struck me that we may be seeing a lot of carbon credits going up in smoke right now,” Shane Moffatt, head of Greenpeace Canada’s Food and Nature campaign, told The Weather Network.

A burnt landscape caused by wildfires is pictured near Entrance, Wild Hay area, Alberta, Canada on May 10, 2023. (Photo by MEGAN ALBU/AFP via Getty Images)

Calculations and canopies

The damage that the BigCoast project saw isn’t an isolated incident. The Bloomberg article that reported on the damage, for instance, also noted that 10 per cent of the Darkwoods carbon offset project, also located in B.C., was burned by fires in 2021. Similar situations have occurred in parts of the United States, including Oregon. The Weather Network emailed Natural Resources Canada asking several questions for this article. In an emailed response to the question about 2BT and carbon offset tree areas damaged by wildfires, the federal agency directed The Weather Network to the Canadian National Fire Database, which takes a year to update and doesn’t include specific data on these areas.

According to Moffatt, Greenpeace has been skeptical about planting new trees as a way for Canada to reach its climate goals. One of the issues is that, quite simply, trees die. A newly planted tree may soak up and store carbon for several years, but it’s susceptible to wildfires, pests, and diseases, all of which may become more severe under climate change.

“And unfortunately, seeing these increasing wildfires may just put a finer point on how impermanent any carbon [reduction] gains from tree planting might be,” Moffatt said.

READ MORE: How climate change 'loads the dice' for more severe wildfire seasons

Victor Lieffers, professor emeritus in forest ecology at the University of Alberta had a slightly more grim thing to say. “Well, all trees eventually die,” he told The Weather Network.

Doing “back of the envelope type” calculations, he estimates that around 4.5 billion trees were killed by fires this year. This is assuming that there are around 1,000 trees per hectare, that 9.5 million hectares were burned, and that the fires killed 50 per cent of the trees per hectare impacted. These numbers are, of course, roughed out for the sake of a quick calculation, and even the number of hectares burned has been updated since The Weather Network spoke with him in mid July.

All the same, Lieffers said that a program like 2BT isn’t likely to be able to keep pace with the number of trees burned in future forest fires. Many younger trees, like those planted as offsets or in the 2BT program, may survive, but it’s not set in stone.

Reforestation. (Lauri Poldre/Pexels)

Never tell trees the odds

How wildfires impact a forested area — whether it’s full of mature trees or recently planted saplings — is a complex science. Gillian Chow-Fraser, boreal program director with CPAWS Northern Alberta, said that older trees can be more resistant to wildfires, considering they contain more moisture than their smaller kin, their crowns are farther from the ground and they often have thicker bark. That said, there are many factors at play.

Biodiversity is an important factor in the long-term health of forests, including replanted ones. This is because a diversity of species reduces the likelihood that all the trees in an area will be taken out by the same pest or disease, and the presence of deciduous trees, which carry more moisture in their leaves than conifers do in their needles, makes a plot less susceptible to fire. By some counts, a reforestation project needs six or seven tree species to be planted. For 2BT-funded projects, 34 per cent of involved planting two to five species, another 34 per cent involve planting six to 19 species, and 32 per cent are 20-plus species of tree. The remaining 10 per cent are projects planting just one type of tree.

According to Jen Beverly, associate professor with the University of Alberta’s faculty of agricultural, life and environmental sciences, these factors include type of vegetation in an area, weather, how densely vegetated the area is, location and many others. In general, though, during the first 20 years or so, areas with newly planted trees tend to be somewhat “fuel limited,” meaning, at least, any fires that occur there won’t be as large. “Under those fuel limited conditions, typically, you're not going to get high intensity fires because there's just not enough fuel there,” she told The Weather Network.

Beverly added that fires can spread through these areas more quickly, but will see a lower intensity in general. In some cases, a fire can rampage through a newly planted area, destroy whatever’s there, then continue burning whatever sources of fuel are nearby. In other cases, these areas can act as fuel breaks, meaning a fire will burn through, run out of fuel, then fail to catch anything else nearby. The fuel break effect could also be strong enough to burn partway through a newly planted area, rather than consuming it all, she said. Lower intensity fires are also easier for humans to douse.

READ MORE: Wildfire smoke may pose risk for brain health

In general, younger trees are less resistant to fire than their more established counterparts, she added. However, some species such as black spruce and jack and lodgepole pine have evolved alongside forest fires. Their bark is quite thin, so they aren’t particularly fire resistant. Plus their pine cones have evolved to crack open during fires, starting a new generation after the older trees are cleared out.

Meanwhile, ponderosa pine trees, found in B.C., have a different relationship with fires. Mature trees have thick bark that lets them survive fairly high intensity fires. Meanwhile, the younger trees are more vulnerable to fires.

“There isn't … a simple narrative around it,” she said.

Chow-Fraser noted that planting and replanting forested areas is important, particularly in areas that wildfires have destroyed. While forests will naturally regenerate, replanting efforts can help “kick start” the process. That said, some are growing back more akin to grasslands and, she noted, forested areas that see multiple fires in quick succession can have their soil stripped of nutrients and seeds, hindering the process.

“If we think of a future where there are more wildfires, where they're bigger, and they're burning more, we need to be thinking about a net gain in forests that we’re actually growing back,” Chow-Fraser added.

French firefighters try to extinguish wildfires in Clova, Quebec, Canada on June 18, 2023. (Photo by SOPFEU / Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

What’s next?

David Wallis, reforestation policy and campaign manager with Nature Canada, said that planting new trees is, indeed, a critical part of reversing the impacts of climate change. However, the “replanting of trees is not going to make up, in the timeframes that we need, for the amount of carbon that is lost through fires and logging,” he told The Weather Network.

The 2BT program has received its share of skepticism over the years. Over the years, some have expressed doubt the federal, provincial, territorial governments, the private sector, and non-profit organizations involved will, collectively, plant two billion trees. More recently, this summer, Energy and Natural Resources Minister Jonathan Wilkinson announced that the government has exceeded its goals in the first two years of the program’s life.

However, the program is actually expected to be a net-positive source of greenhouse gas until 2031, according to a report from the federal government, and capture only 4.3 megatonnes of carbon dioxide or equivalent by 2050, a far cry from the program’s goal of reducing emissions by 12 megatonnes by that year.

The report also noted that this dip comes from emissions from planting trees, and preparing the areas, considerations Wallis also brought up along with moving people around to plant the trees, and the energy it takes to grow trees up from seeds. According to the email from NRCAN, the 2BT program encourages groups involved to use native, locally- or regionally-sourced trees.

WATCH BELOW: What role does climate change truly play in wildfires?

Wallis added that the emissions reductions from the 2BT program assumes a 100 per cent survival rate of the trees. He said this is unreasonable “because they will know even the best tree planting project in the world will not have 100 per cent survival.”

He added that, in the case of the 2BT program, there should be a bigger emphasis on co-benefits, such as planting trees in urban areas to improve human health, and restoring habitats for critically endangered species, like the woodland caribou.

The emailed response from NRCAN notes that the program “aims to fund projects that demonstrate greater co-benefits,” including habitat restoration and “increased human well-being.” The email also noted that, as part of the application process, interested parties need to provide a long-term maintenance plan, including plans on how to “manage any cases in which there are substantial tree [mortalities].”

According to Moffatt, there are other concerns about using tree planting to meet Canada’s climate goals. While stopping fossil fuel emissions would be an “immediate gain,” waiting for trees to grow takes time, assuming they even do. Rather, he said, it makes more sense to hand forested areas back to Indigenous governance and management, including fire management strategies like cultural burning, which is somewhat akin to prescribed burning.

Chow-Fraser added that it’s important for Canada to think about its tree-planting efforts in a particularly wildfire-ridden future. “It … raises the stakes for these replanting programs, for sure. You don't want to be putting all of this work in and then see another fire move through and kind of get you back to point zero,” she said.

Thumbnail image: A view of wildfires at Lebel-sur-Quevillon in Quebec, Canada on June 23, 2023. (Photo by FREDERIC CHOUINARD /SOPFEU / Handout/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)