What’s needed to get EVs into rural Canada?

Range, a dearth of charge stations, and price are among the key reasons for rural and remote communities’ lacklustre adoption of electric vehicles. Non-profits, governments, and companies are aiming to change this.

Canada saw more than 86,000 electric vehicles added to its roads in 2021. According to the Canada Energy Regulation, this bump in vehicles registered accounted for 5.3 per cent of total registrations that year, and marked a new record for EV adoption in the country.

But huge swathes of the country remain largely free of EVs, namely the rural and remote areas. Experts told The Weather Network that some of this comes down to misconceptions, and some of the technical problems with driving an EV in rural areas are being addressed. But, for now, many communities are still reluctant to adopt the low-emission vehicles, or simply lack the ability to do so.

According to a 2021 poll, the top three concerns amongst Canadians for EVs were limited driving range, price, and lack of public charging infrastructure. In all three, rural respondents were more likely to express concern than other parts of the country. In the case of limited driving range, 61 per cent of rural respondents listed the reason, compared to 50 per cent of urbanites.

READ MORE: This van takes air pollution testing to the source

In the case of rural British Columbia, EVs can be seen driving around, according to Sarah Sinclair, digital media and project co-ordinator with the BC Rural Centre. But often, their drivers aren’t full-time residents, she explained. Rather, they might be short-term renters, vacation homeowners, or people who searched for properties outside the city during the pandemic.

According to Sinclair, many people in the rural or remote parts of B.C. may indeed want to purchase an EV but there are hurdles that need to be overcome first.

“We all love where we live and we love the environment. And we don't want to be seen as part of the cause of more greenhouse gasses, more climate change,” she told The Weather Network.

Here are a few of the barriers to EVs in rural and remote areas, and what’s being done to address them.

They’re too expensive

Sinclair also heard some of the concerns raised in the 2021 poll. For example, not everyone can afford an electric vehicle, she said. According to Scotiabank, the cost of a new EV in Canada can run between $32,000 and $160,000, depending on the model.

While this is generally true, there are also lower-priced EVs and their operating costs are lower than gas-powered cars, according to Cara Clairman, president and CEO of non-profit group Plug N’ Drive. Electricity, for instance, is cheaper than gas, and they have to be repaired less frequently, though she acknowledged that finding a mechanic capable of repairing an EV in rural Canada might currently be difficult, though this could change going forward.

“So, even if you do pay a little bit more upfront for the car, you're saving a bundle over time,” she said.

Finally, she noted that car manufacturers have mostly been rolling out EVs in small batches so far, eliminating the economies of scale that can keep prices down, but this could also change in the future.

“You know, we're still in the early days,” she said.

“I think time will tell, but my guess is that … it won't be long before we would have those sorts of really low-priced vehicles,” she added.

A rural road seen near Whistler, B.C., in 2018. (Pedram Farjam/Pexels)

Everything is farther apart in rural Canada, and EV range is limited

Some people in rural B.C. avoid purchasing an EV because of range, Sinclair said. This is fine for short trips to a nearby town, but not for longer treks, at least not without adequate charging station infrastructure. (The median driving range of EVs was around 377 kilometres, compared to gas-powered vehicles at around 649 kilometres in 2021.)

How well an EV fits a rural person’s lifestyle depends on several factors, including how far they drive on a typical day. While the lack of charging infrastructure may be an issue for people taking long-haul treks, such as people living in particularly remote areas, most people living rurally live somewhat near a town, and take a longer trip to a city or for a vacation a few times in a year, Clairman explained.

She added that urban and suburban drivers have, indeed, been the early adopters of EVs.

“But I think, in reality, we would find that there's a lot of rural people where an EV would be well suited to their lifestyle,” she told The Weather Network.

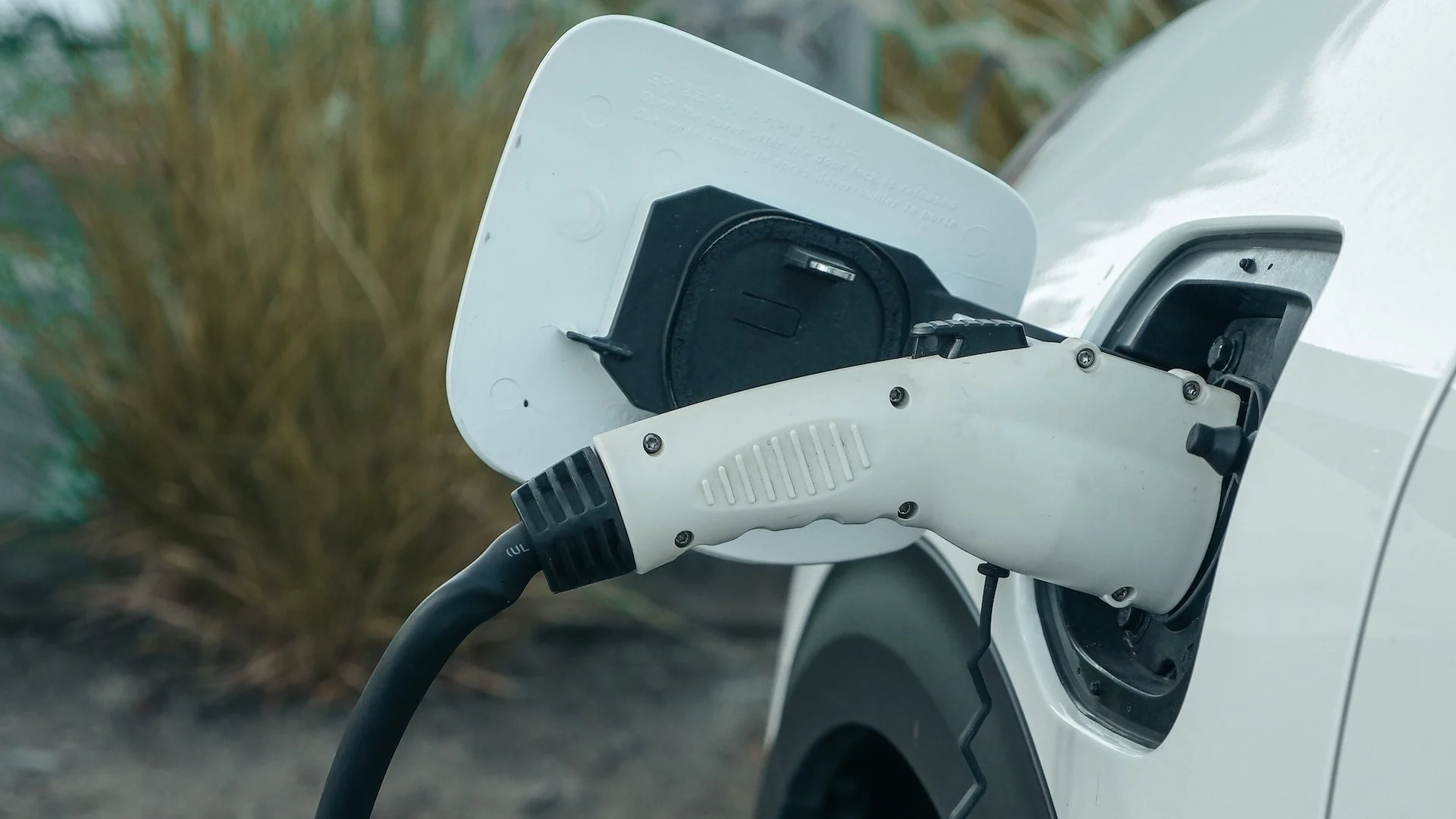

An electric vehicle fuelling up at a charge station. (Kindel Media/Pexels)

There aren’t enough charging stations in rural and remote areas

Largely, rural Canada doesn’t have the same number of EV charging stations as urban areas, though there are numerous efforts to grow this number, including in the Kootenays, where Sinclair lives. That said, charging an electric car can tack extra time onto what could, otherwise, be a shorter trip.

According to Devin Arthur, industry expert with the Electrical Vehicle Society, getting charging stations installed in rural remote areas could pose something of a problem. Many communities in these parts of the country won’t get the same amount of traffic as major corridors, like between Windsor and Montreal. As such, private companies might find it harder to justify installing them there, as they wouldn’t recoup the installation costs right away.

“But at the same time … you need to have that infrastructure to give public confidence that they can drive an electric vehicle,” he told The Weather Network.

The federal government has announced funding for EV chargers in some rural and Indigenous communities. The private sector is also trying to find ways to make charging stations reach these locales.

Three transmission towers seen at dusk. (Pok Rie/Pexels)

Rural grids can’t handle everyone charging their EVs

Yet another concern is the power grid in rural and, in particular, remote areas, which may not be able to handle a huge influx of EVs all needing a charge according to Sinclair. Sometimes, in the Kootenays where she lives, the power can go out for dozens of hours, “and you have to get your kids to school, or you have to get to work yourself, and you can see a power outage for over 24 hours. That's not really a feasible implementation,” she said.

Additionally, some of Canada’s nearly 300 remote communities rely on burning diesel to generate electricity. This generates emissions, and potentially offsets the climate benefits of EVs, though only 0.7 per cent of Canadians lived in communities deemed “most remote.”

For his part, Arthus said that he doesn’t think this will be a problem long term. While some areas have older infrastructure, they’re being repaired and updated by degrees anyway. For instance, the federal government has funding slated for rural and remote communities to improve their power grids.

These improvements could be used to power EVs as well, Clairman said. She added that when gas-powered vehicles first hit the market, gas stations weren’t widely spread across the country either.

“So, it just takes some time,” she said.

Thumbnail Image: An electric vehicle at a solar charging station surrounded by trees, seen in 2021. (Kindel Media/Pexels)