Scientists recently checked up on Earth's 'vital signs.' So how are we doing?

Scientists have given the planet a checkup — and all is not well.

A major new report on what the authors describe as the world's "vital signs," published Tuesday in the journal BioScience, presents a grim picture of where the planet is headed.

The assessment was prepared by some of the world's top climate scientists and builds on a previous analysis backed by more than 15,000 scientists.

SEE ALSO: Could climate change bring paradigm shift in biodiversity tracking?

Entitled "The 2024 state of the climate report: Perilous times," the assessment found that 25 of the 35 of the measurements used to track the planet's climate risk, from ocean temperatures to tree cover loss, are at record levels.

These measures look at both how humans are changing the planet, and how the planet is responding.

"We are on the brink of an irreversible climate disaster," the authors wrote. "This is a global emergency beyond any doubt."

New Zealand deforestation. (Getty Images-1497731928/Philip Thurston).

At the same time, the report also found some surprising signs of progress that experts say point to a path forward. And that's where we'll start.

Some environmental progress

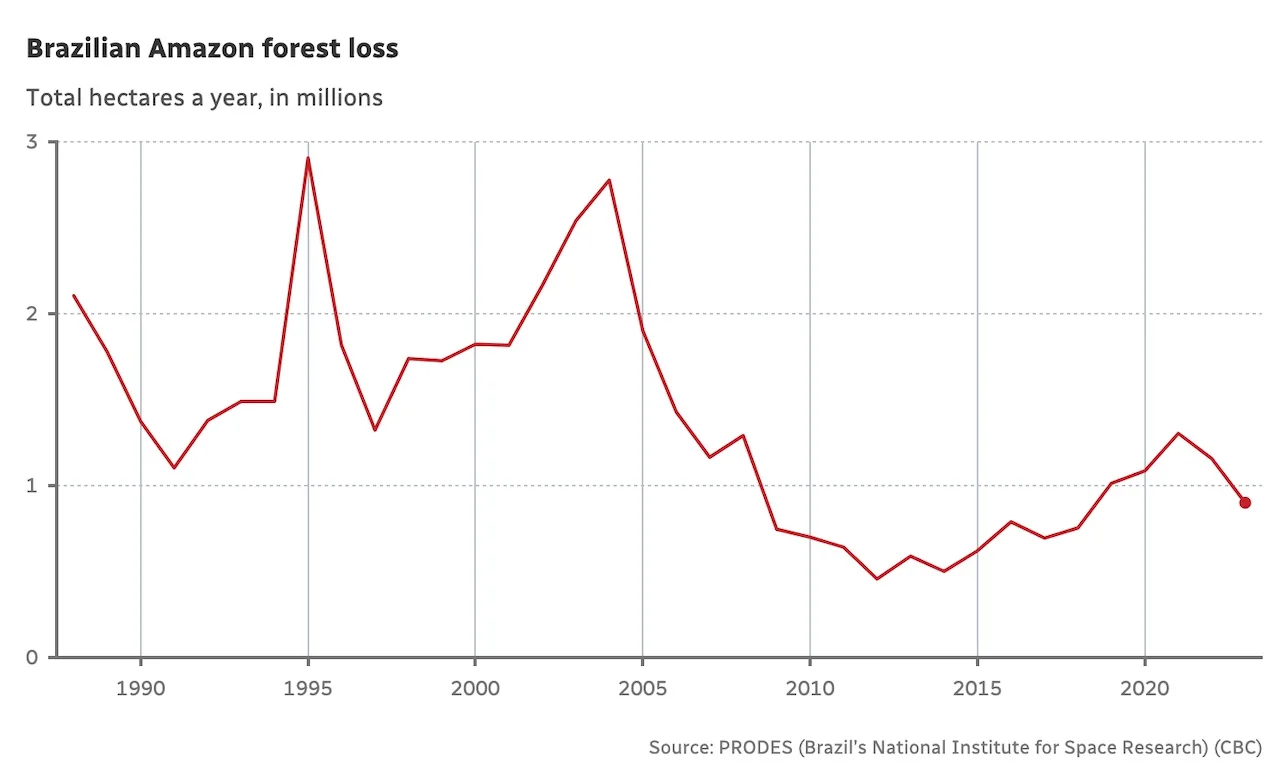

Two charts in the report show signs of environmental progress.

The first looked at how much of the Amazon rainforest has been lost every year. In recent years, the rate of deforestation has declined.

(PRODES (Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research) (CBC))

William Ripple, lead author and professor at Oregon State University, calls the Amazon development "really important good news," which he attributes to new conservationist leadership in Brazil.

The rainforest stores an estimated 123 billion tonnes of carbon, according to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, roughly equivalent to four years of global emissions if it were to be released as CO2.

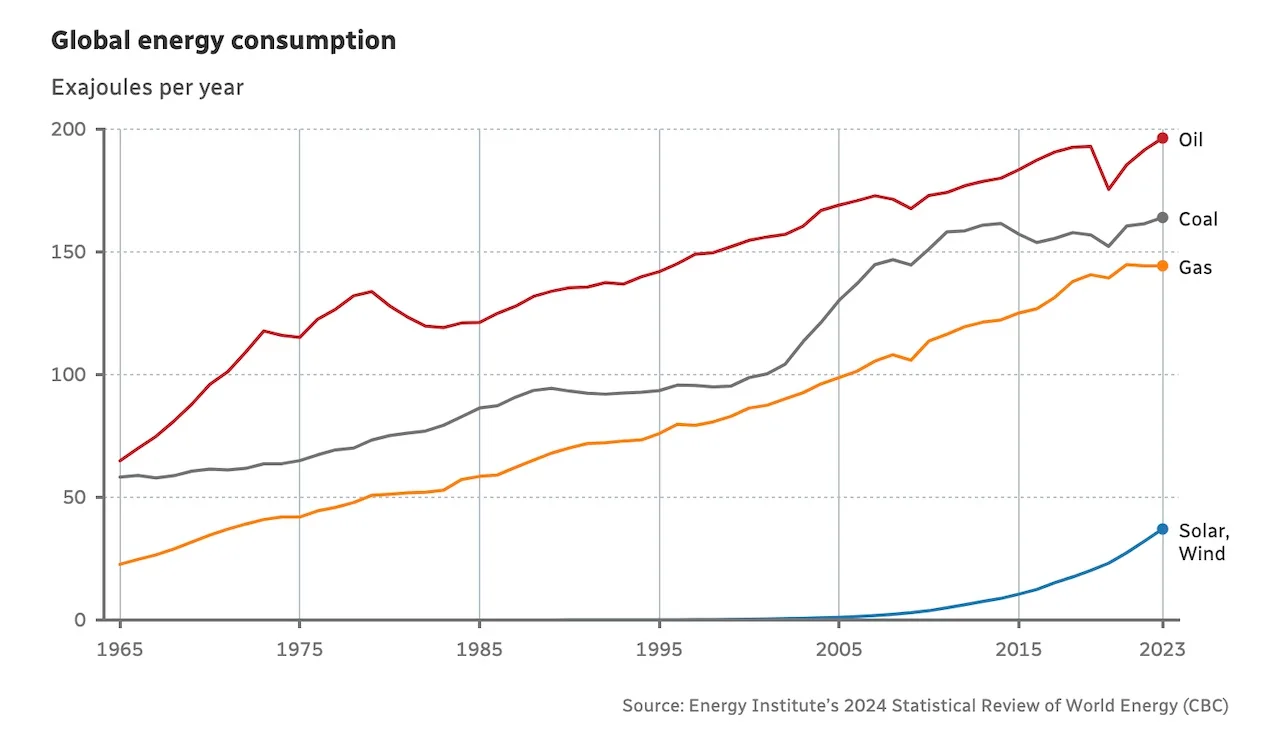

The other chart looks at how much energy consumption can be attributed to renewable energy.

The production of renewables has surged, as the chart shows — although the amount of oil, coal and gas also continues to climb. Climate change is driven primarily by the burning of fossil fuels.

"Solar and wind energy are increasing dramatically," Ripple said. "It's still many times lower than fossil fuel, but the trend is deep and upward — and that is promising."

(Energy Institute’s 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy (CBC))

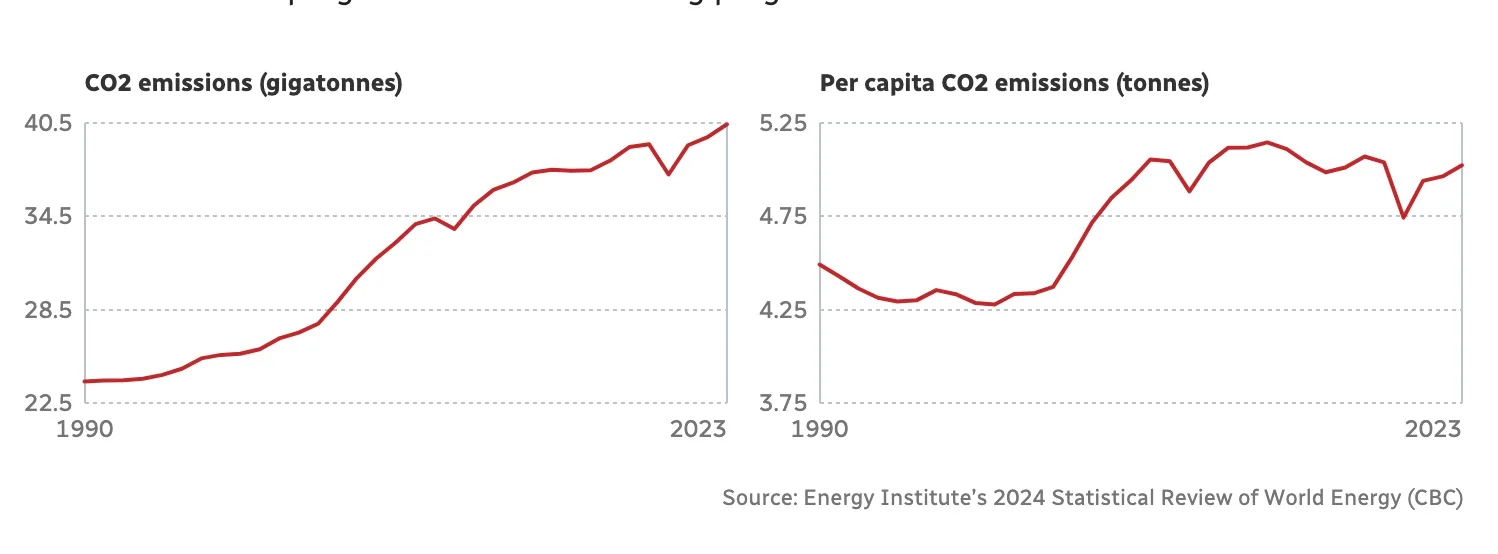

Emissions still climbing

Overall, however, we are emitting more greenhouse gases than ever, on both a global and individual level.

Prof. Sarah Burch, executive director of the Waterloo Climate Institute, says she sees a glimmer of hope in the face of these numbers.

Burch said even though fossil-fuel consumption hasn't levelled off or declined, it is slowing down — and ultimately that could lead to a more clear shift in how we produce energy.

"That's just how things change," explained Burch, who was not involved with the report.

She warns that this doesn't mean we shouldn't be "more ambitious, more creative and more honest about our progress. But we are making progress."

(Energy Institute’s 2024 Statistical Review of World Energy (CBC))

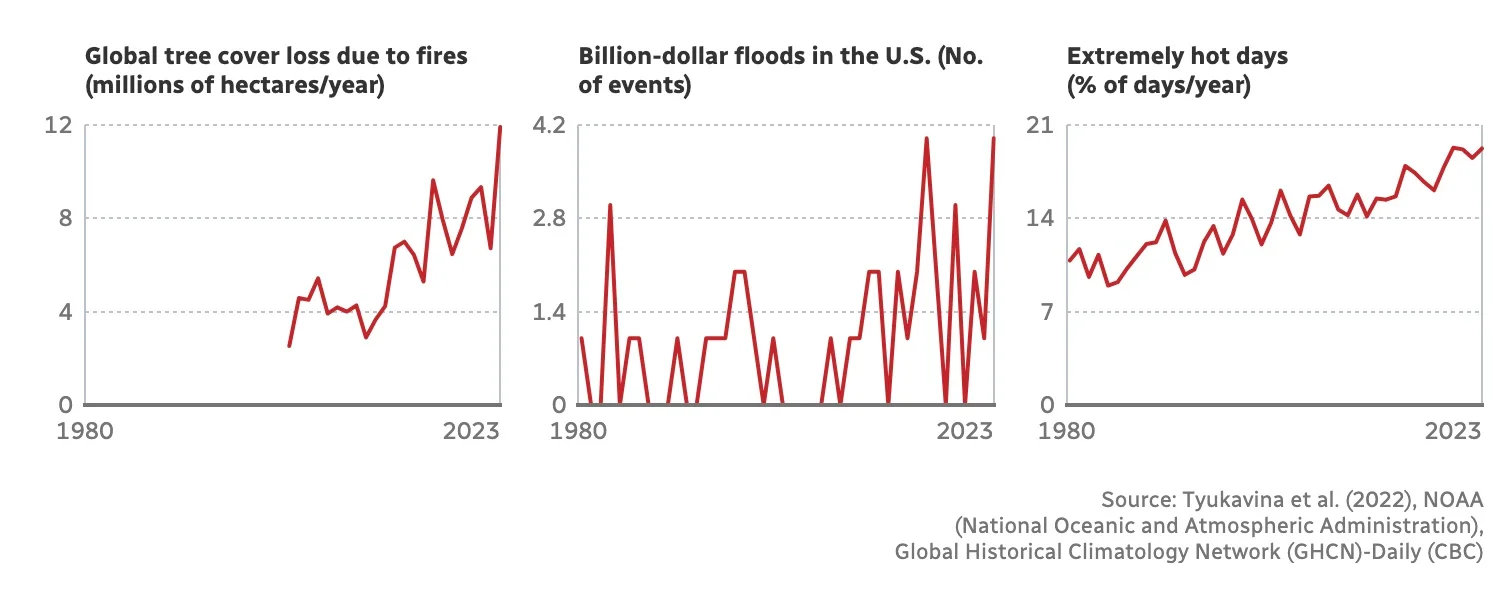

Climate-related disasters

These next charts from the report illustrate how devastating climate-related disasters have been.

Wildfires and floods are on the rise around the world, and the planet is experiencing more and more days of extreme heat.

"We're having these heat waves and floods and hurricanes and they're becoming more frequent and more intense and leaving trails of devastation worldwide," said Prof. Jillian Gregg, an ecologist at Oregon State University who also contributed to the report.

Canada has seen this first-hand, with the 2023 wildfire season smashing records, followed by another quietly devastating year in 2024.

The increase in extreme weather, Ripple says, is exemplified by last month's Hurricane Helene, which devastated parts of Florida and North Carolina.

He pointed out that even Asheville, N.C., which had been celebrated as a "climate haven" because of its temperate weather, wasn't safe from a storm like Helene, which was made more powerful more quickly by our warming oceans.

(Tyukavina et al. (2022), NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), Global Historical Climatology Network (GHCN)-Daily (CBC)

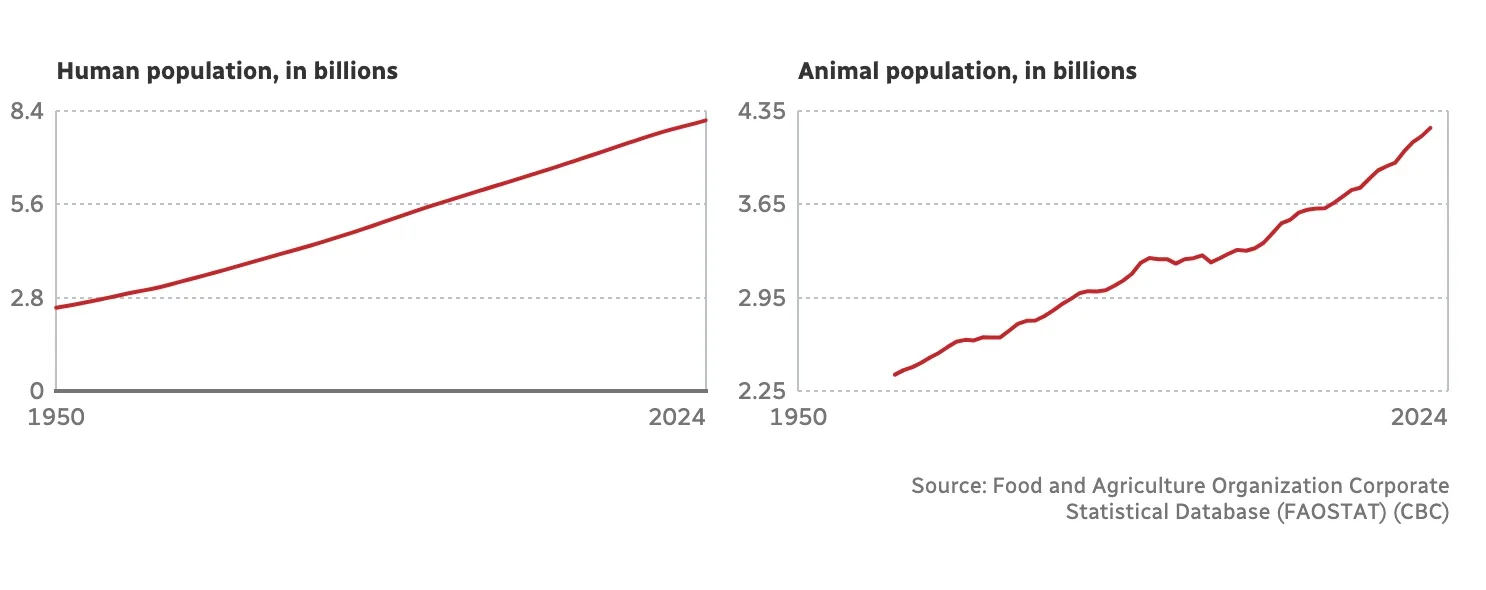

We're growing, we're eating

As these disasters play out, the world's population continues to grow, and we are producing — and eating — more livestock every year.

The ruminant livestock population, which includes animals such as cows, sheep and goats, is a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions.

It is increasing at a pace of roughly 170,000 animals per day, according to the report.

While fossil fuels are the main driver of climate change, agricultural emissions, which include methane, are also a significant contributor.

According to Our World in Data's analysis of UN figures, an estimated 80 per cent of agricultural land on the planet is used for grazing and growing feed for livestock.

(Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT) (CBC))

A negative feedback loop occurs as food production is then threatened by drought and other extreme weather events, strengthened and lengthened by climate change.

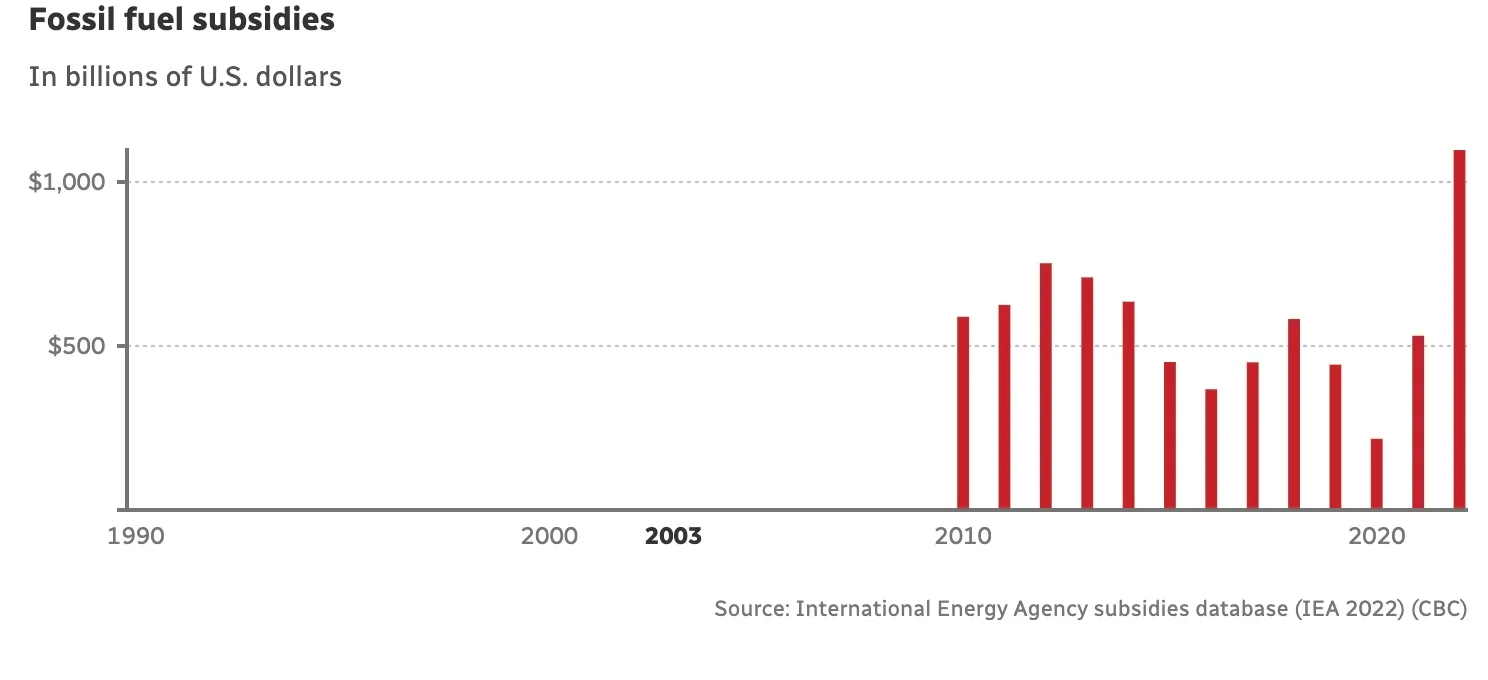

Funding the fuel

The last chart shows the subsidies provided to the fossil fuel industry, a dynamic experts say has, for years, delayed the transition to renewable energy.

Many international organizations have called for an end to fossil fuel subsidies, and according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), global subsidies surpassed $7 trillion US for the first time last year, with Canada doling out $2 billion in fossil fuel subsidies.

International Energy Agency subsidies database (IEA 2022) (CBC)

"It's not remotely a level playing field," said Naomi Oreskes, another co-author and a history of science professor at Harvard University.

"If we were to wipe out all subsidies all together, renewable energies would beat the pants off of fossil fuels."

WATCH: Flooding is the number 1 cost of climate change

Thumbnail courtesy of Ben Nelms/CBC.

The story was originally written by Benjamin Shingler, Anand Ram, Wendy Martinez and published for CBC News.