Astronomers bolster case for potential of life on one of Jupiter's moons

Astronomers bolster case for potential of life on one of Jupiter's moons, Europa

In the search for life in our solar system, the discussion typically revolves around Mars. But there are two moons many astronomers believe are even better bets: Saturn's moon Enceladus and Jupiter's moon Europa.

Now a new computer model by NASA scientists lends further support to the theory that, beneath the thick, icy crust of Europa, the Jovian moon's interior ocean could be habitable.

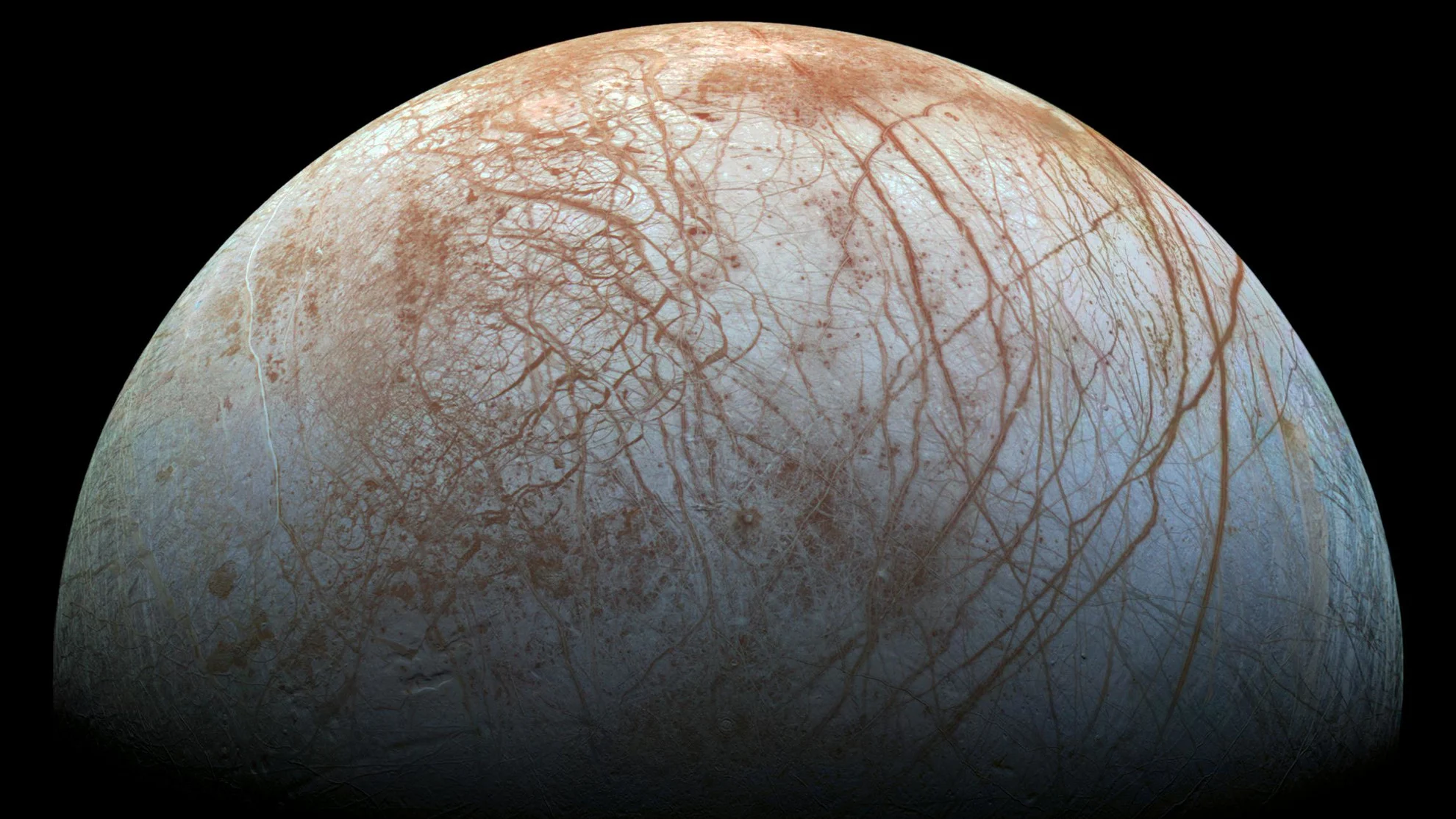

Europa is the sixth-largest moon in the solar system, smaller than the Earth's moon but larger than Pluto.

The scientists believe the moon's ocean may have formed after water-rich minerals released their water due to heating caused by the radioactive decay of the satellite's core. Due to its gravitational interactions with gas giant Jupiter and with other moons, the water is kept warm.

But not all water means life. Other important building blocks are needed, and researchers believe that was the case.

'THIS OCEAN COULD BE QUITE HABITABLE'

Billions of years ago, the ocean would have been mildly acidic, but with concentrations of carbon dioxide, calcium and sulfate too high for life as we know it.

"Our simulations, coupled with data from the Hubble Space Telescope, showing chloride on Europa's surface, suggests that the water most likely became chloride-rich," said Mohit Melwani Daswani, a geochemist and planetary scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, who presented the recent findings at the virtual Goldschmidt conference this week.

"In other words, its composition became more like oceans on Earth. We believe that this ocean [now] could be quite habitable for life."

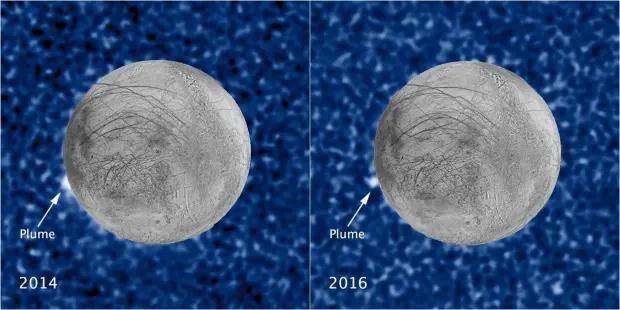

Observations of Europa by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope uncovered a probable plume of material erupting from the moon's surface at the same location where a similar plume was seen two years earlier by Hubble. Astronomers believe that this is more evidence of liquid water below its icy surface. Credit: NASA/ESA

Water and minerals aren't the only thing needed for life. Life needs energy.

"It's unlikely that any possible life forms in Europa's ocean would use sunlight as a source of energy, because Europa is really quite far from the sun, and the ocean would be under complete darkness beneath a really thick ice shell," Melwani Daswani said. "So we have to think about other sources of energy."

On Earth, life exists around hydrothermal vents, openings on the ocean floor that emit dissolved minerals, and there has been strong evidence that these may exist in Europa's subglacial ocean as well. That could be used as a source of energy for any potential life.

Melwani Daswani is cautious.

"We don't even know whether life as we know it would be happy over there or whether the energy available for that for life would be sufficient," he added.

MISSION TO EUROPA

Gordon Osinski, a professor in the department of Earth sciences at Western University in London, Ont., who was not involved in the study, said that this new research is another reason that missions to moons like Europa or Enceladus are so intriguing.

"I think the key take-home here is that these ocean worlds present the best likelihood for present-day habitable environments," he said. "So, life living on those planets at the present day. All the key ingredients are there."

NASA does have a mission in the works to visit the moon: the Europa Clipper.

The mission — the first dedicated mission to a moon other than our own — won't be looking for signs of life, since it will only orbit, but it will look for increasing evidence of potential habitability by studying its geology, icy shell and composition.

Osinski said that it would be ideal for a future sample-return mission, where a spacecraft could even fly through and collect from plumes of water vapour that have been seen blown into space by both Europa and Enceladus through fissures in the ice.

"Because then we'll know," he said. "We'll have the unequivocal determination of whether there is life there or not."

This article, written by CBC Senior Science Reporter Nicole Mortillaro, was originally published for CBC News