'Needle in a haystack' black hole spotted outside our galaxy

This 'dormant' black hole apparently completely collapsed in on itself without so much as an errant flash of light.

Astronomers have found a true oddity — a 'quiet' black hole that resides outside our Milky Way Galaxy.

Roughly 160,000 light years away, in a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way known as the Large Magellanic Cloud, lies the Tarantula Nebula. This bright expanse of space dust and gas glows from the energies of the massive stars being born, living, and dying there.

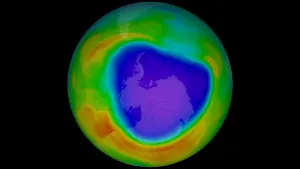

This image of the star-forming region of the Large Magellanic Cloud, known as the Tarantula Nebula, combines infrared and radio observations from different instruments and telescopes that are part of the European Southern Observatory. Credit: ESO, ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)/Wong et al., ESO/M.-R. Cioni/VISTA Magellanic Cloud survey/Cambridge Astronomical Survey Unit

After scanning around 1,000 massive stars in this region of space using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT), a team of astronomers discovered something remarkable.

"We identified a 'needle in a haystack'," Tomer Shenar, the astrophysicist who led the new study, said in an ESO press release.

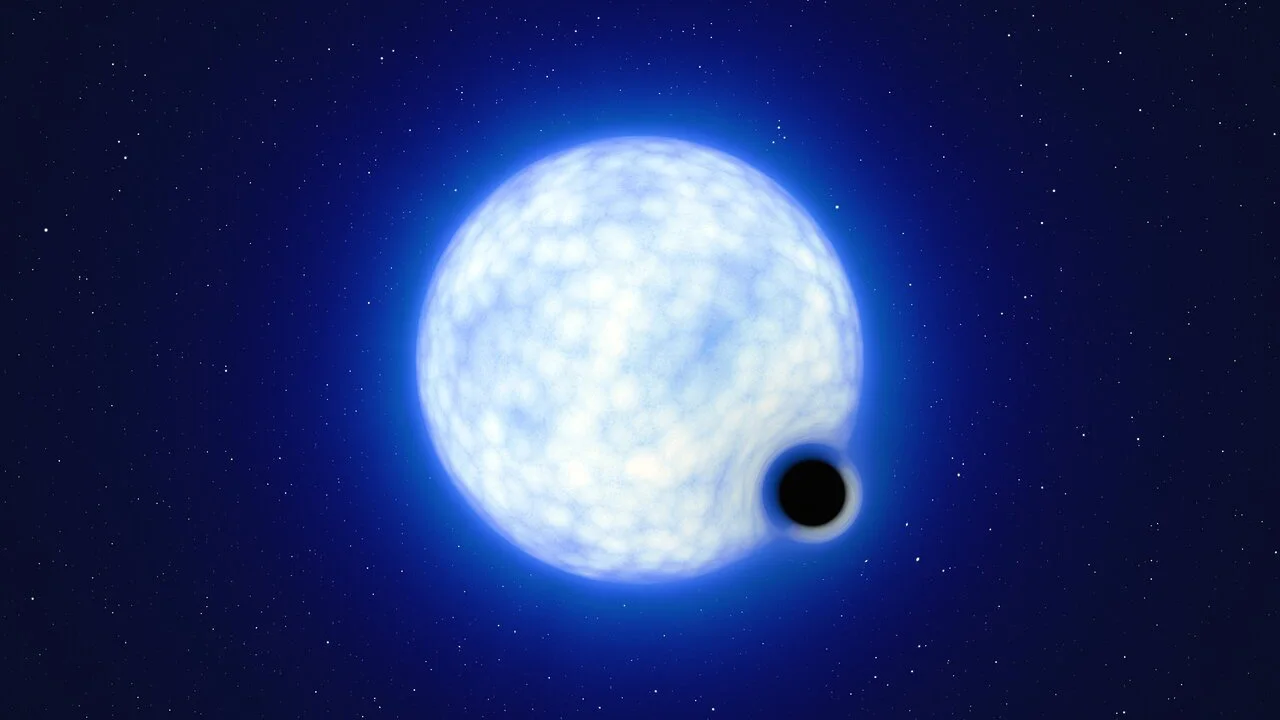

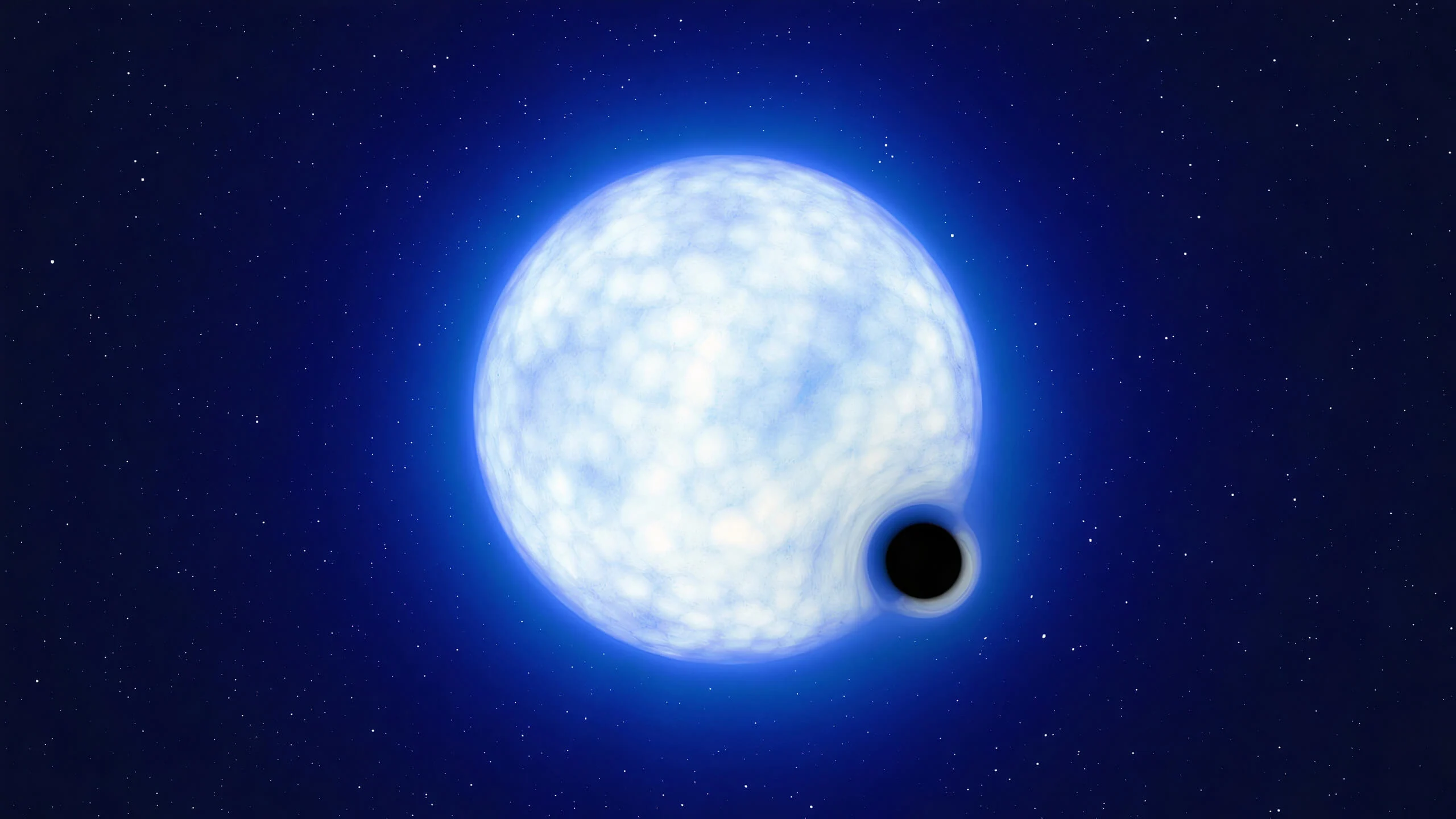

A bright blue star, around 25 times the mass of our Sun, was found to have a small companion orbiting around it. This companion emits no light of its own and tips the cosmic scales at around 9 solar masses. Those two facts together pointed to it being a black hole, but if so, it was a very unusual specimen.

Most black holes of this type ("stellar-mass" black holes) are spotted due to the high-energy x-rays they emit as they gobble down matter they pull off a companion star. The first black hole ever detected, Cygnus X-1, is an example of this.

However, this black hole, named VFTS 243, is completely quiet, or "dormant," as its discoverers call it.

This artist's illustration shows what this binary system VFTS 243 probably looks like, with a small black hole companion orbiting around a giant bright blue star. Credit: ESO/L. Calçada

Dormant black holes are thought to be pretty common. They are difficult to find, though, because they don't emit radiation that can be used to locate them. While claims of similar discoveries have been made in the past, none were apparently as compelling as this one.

"For more than two years now, we have been looking for such black-hole-binary systems," co-author Julia Bodensteiner, an astrophysical researcher with ESO in Germany, explained in the press release. "I was very excited when I heard about VFTS 243, which in my opinion is the most convincing candidate reported to date."

"As a researcher who has debunked potential black holes in recent years, I was extremely skeptical regarding this discovery," Shenar remarked.

"When Tomer asked me to double check his findings, I had my doubts. But I could not find a plausible explanation for the data that did not involve a black hole," said Kareem El-Badry of the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, who is known as the 'black hole destroyer' for his work in debunking so-called discoveries.

This study, to be published soon in the journal Nature Astronomy, was conducted by an international team of 38 scientists, including two Canadians — Vincent Hénault-Brunet from Saint Mary's University in Halifax, and Anthony Moffat from the University of Montreal.

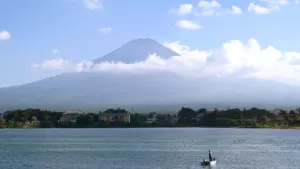

This image of the Tarantula Nebula from VLT Survey Telescope at ESO's Paranal Observatory in Chile shows a zoomed in look at the region around VFTS 243. Credit: ESO

Finding a dormant black hole orbiting around a companion is rare enough. The two must be so far apart that the black hole's gravity can't syphon off a significant amount of the blue star's material.

One other discovery about VFTS 243 makes it even more of a rarity.

Based on their research, the astronomers believe that this black hole completely consumed the star it formed from.

In many cases, a stellar-mass black hole results from a massive star dying in a cataclysmic supernova. The star uses up the last of its resources for fusion, which cuts off the source of pressure that keeps the star's outer layers aloft. Those outer layers then come crashing down, crushing the core into an infinitesimally small point known as a singularity. In the process, there is usually a backlash that blasts outward, ripping the outer layers apart and flinging them out into space as an immense expanding cloud of stellar debris. This spectacularly bright explosion is a supernova.

If the black hole has a binary companion, the gravity of the expanding debris cloud will pull on that companion star, disturbing its original orbit over time. So, finding a companion star with a circular orbit around a black hole would be next to impossible, or at least extremely rare.

However, the black hole and companion star that make up VFTS 243 were discovered to have nearly circular orbits around each other.

For that to be the case, it's likely that the dying star did not produce a supernova. Instead, as the star's core collapsed into a singularity, it apparently dragged the rest of the star's mass down with it!

"The star that formed the black hole in VFTS 243 appears to have collapsed entirely, with no sign of a previous explosion," Shenar explained.

"Evidence for this 'direct-collapse' scenario has been emerging recently, but our study arguably provides one of the most direct indications. This has enormous implications for the origin of black-hole mergers in the cosmos."