Hurricane Idalia was so intense it may have blunted future storms

The powerful hurricane churned the Gulf of Mexico so much that it may affect the intensity of future storms

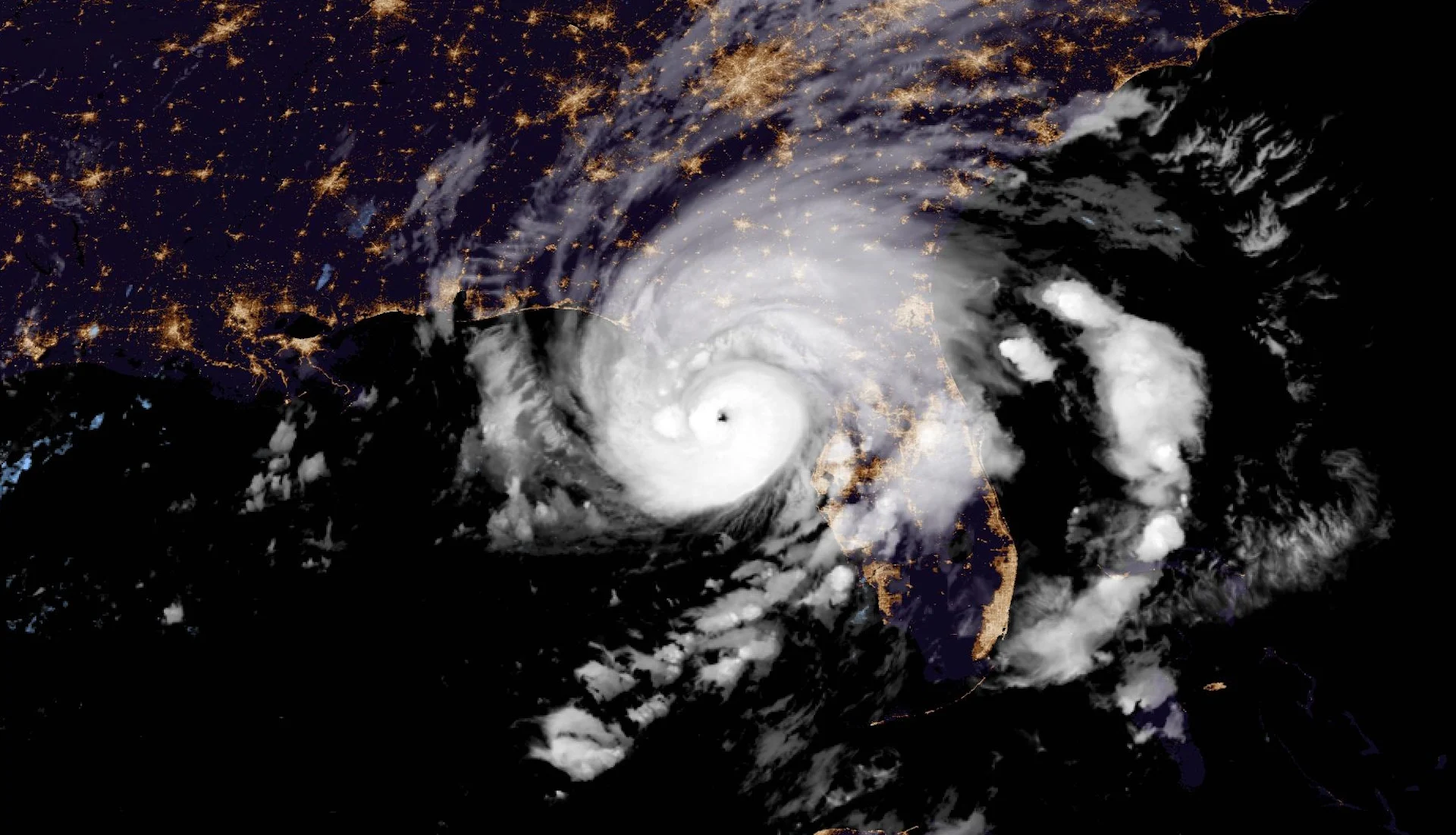

Hurricane Idalia nearly doubled its strength in the 24 hours before the major hurricane made landfall in northern Florida on Wednesday, August 30.

Idalia’s size and intensity pushed the ocean into the coastline, generating a storm surge and rough waves that collectively towered several metres high in spots.

Visit The Weather Network's hurricane hub to keep up with the latest on tropical developments in Canada and around the world

The storm rapidly intensified over the Gulf of Mexico in large part due to the abnormally warm waters that lined the storm’s path—and Idalia’s effect on the very waters that fuelled it may temporarily stunt any future storms that enter the eastern Gulf in the weeks ahead.

Idalia joined an infamous group of rapidly intensifying storms

Idalia reached hurricane strength at daybreak on Tuesday, August 29, only to undergo a tremendous strengthening trend over the next 24 hours.

By sunrise the following morning, Idalia had explosively intensified into a monstrous Category 4 hurricane with maximum sustained winds of 215 km/h.

RELATED: The curse of storm nine: Why so many “I” hurricanes are monsters

This represented a stunning jump in the storm’s intensity over a 24-hour period, an intensification that would take a ‘typical’ high-end storm days to achieve.

Hurricane Idalia’s rapid intensification as it swirled toward landfall follows a terrifying pattern we’ve seen across the Gulf of Mexico in recent years, including historic storms such as Harvey in 2017, Laura in 2020, Ida in 2021, and Ian just last year.

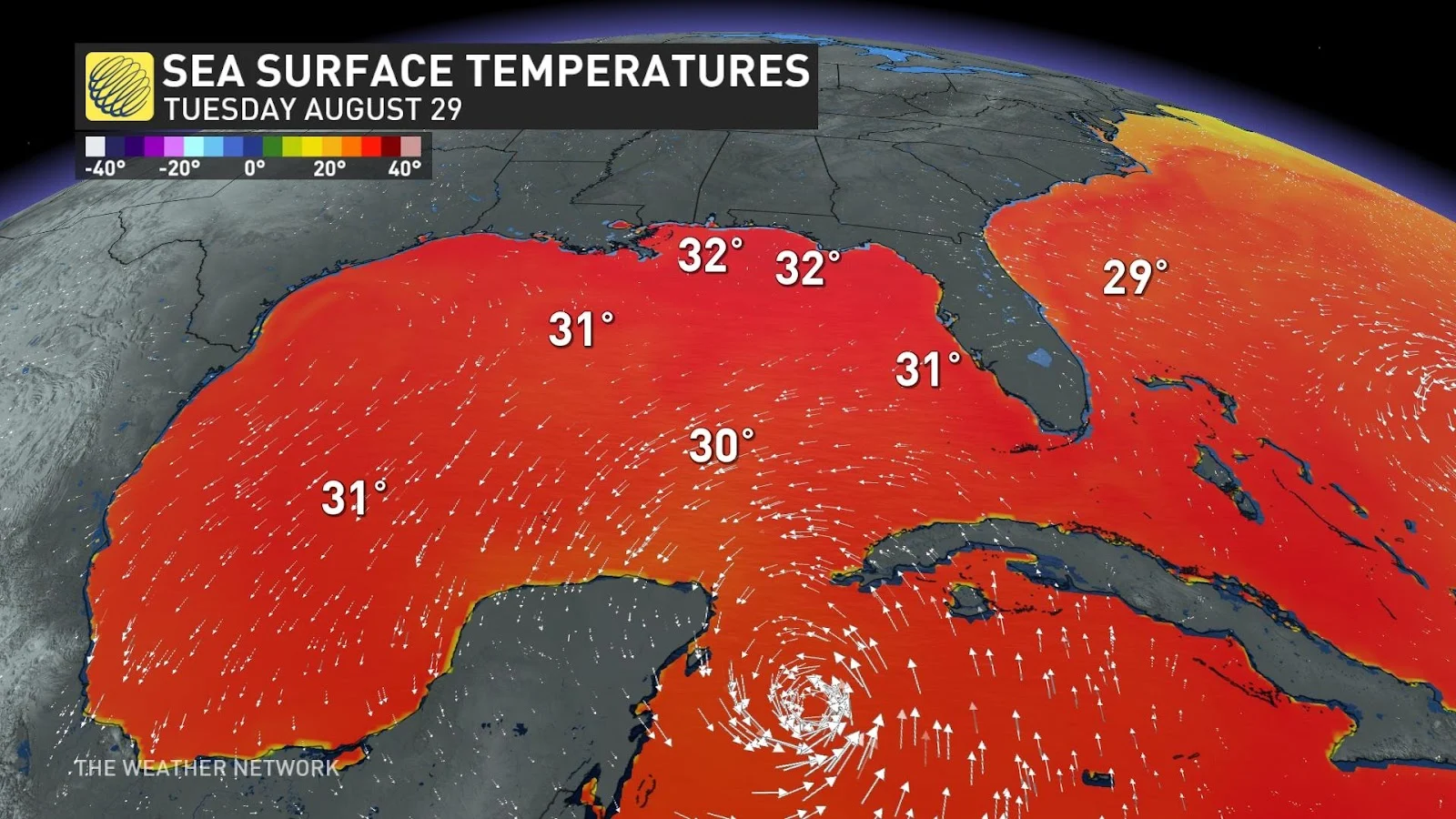

Very hot ocean waters fuelled Idalia’s rise

Much of that intensification is the result of bath-like ocean temperatures throughout the Gulf of Mexico, where sea surface readings often exceeded 30°C in the days leading up to Idalia’s arrival.

Warm water is a critical ingredient in the development of a tropical system. Much like you’d blow on a hot cup of coffee to cool it off, a growing storm’s winds blow over the surface of the ocean and evaporate a tiny layer of hot water. This steamy water vapour rises into the storm and releases its heat when it condenses.

DON’T MISS: How hot water fuels the world’s most powerful hurricanes

A hotter ocean has the opportunity to release more heat inside of a hurricane, which fuels the powerful thunderstorms in the eyewall that serve as a hurricane’s engine.

When atmospheric conditions are favourable for a storm to grow, extremely warm ocean waters can send a hurricane into hyperdrive, so to speak, allowing the system to rapidly intensify at a frightening pace.

WATCH: Idalia declared region's strongest hurricane in 125 years

Hurricanes ultimately cool the waters that fuel them

Hurricanes are a stunning example of how all weather stems from nature’s futile attempt to seek balance and harmony. Low pressure begets high pressure. Extreme heat begets extreme cold.

A tropical cyclone’s ‘purpose’ is to transport excess heat from lower latitudes toward the poles. For all of their violence, hurricanes are one of nature’s many attempts to seek peace.

STAY SAFE: What you need in your hurricane preparedness kit

When a hurricane like Idalia rages over those bath-like ocean waters, the storm churns the very ocean fuelling its explosive growth. The sloshing waves and forceful surge on the ocean surface induces a process called upwelling—water from deep in the ocean rising toward the surface.

Upwelling is very common around the world. If you’ve ever visited southern California, Chile, or South Africa, the ocean is chilly there because deep currents run up against the land and send frigid waters rising to the surface.

Strong hurricanes churn the water so much that they also create upwelling in their wake. Cooler water rising to the surface can leave the ocean relatively chillier than it was when the storm arrived.

This cooling effect can stick around for days and even weeks after a storm, potentially stunting the development of any storms that follow.

Idalia’s upwelling isn’t a sure bet against future storms

While ‘cooling’ is a relative term at the peak of hurricane season, the Gulf of Mexico was running a fever when Idalia passed over the region. The region’s 30-degree water temperatures ran more than 50 m below the surface, proving just how deep and widespread the unusual warmth is this year.

Even though the water is still plenty hot enough to sustain a hurricane off Florida’s western coast, it’s not quite the rocket fuel it was just a week ago, which might blunt any storms that pass through the eastern Gulf as we move through September.

DON’T MISS: The best way to prepare for a hurricane is well ahead of a potential disaster

However, Idalia’s upwelling isn’t a bulwark against future storms. We saw plenty of powerful systems roll through the Gulf in 2020, which saw the most active Atlantic hurricane season on record.

Hurricane Laura hit Louisiana near scale-topping intensity in August 2020. That storm also induced upwelling in the Gulf of Mexico in its wake. But that cooling effect wasn’t enough to stop several more major hurricanes from strengthening over those same waters several weeks later, including Hurricane Sally, Hurricane Delta, and Hurricane Zeta.

Header image of Hurricane Idalia on August 30, 2023, courtesy of NOAA.